We're really excited about some new curriculum thinking that holds huge potential for kids and schools. Here's how we got here.

The first time I got really provoked about curriculum issues was when Coalition of Essential Schools Founder Theodore Sizer visited our school in the early 90’s. He spent most of a day and seemed to have had a great visit, roaming around the school on his own for several hours, asking students about their experiences. On his way out, after a few glowing remarks about the climate, he asked, with a curious look, “You know, schools are funny. I wonder why we’ve decided to offer American History in the morning, but American Literature in the afternoon?” He asked it lightly, in a tone that suggested he wanted me to think on it more than he wanted an answer. That would be Ted.

As a busy high school principal, I didn’t give it a whole lot more thought that day, but it came back to me that evening, and again the next day. That simple question from Ted led to weeks, and ultimately years of thinking about how we order things, how, in Jal Mehta’s words from The Allure of Order, we attempt to “rationalize” human learning and school behaviors. Ongoing deliberation on his question led our school to move eagerly to a Humanities format that included those two traditional fields, or “classes”, that Ted mentioned, but also social sciences, music, art and design, themes re-cast in deep exploration of issues that matter to us all, that go beyond simple notions of “inter-disciplinary”.

A decade later, I, like 15 million other viewers, chuckled and nodded through Sir Ken Robinson’s TED Talk- “do schools kill creativity?” Of course, they do. We know that. They are meant to instill conformity instead. But in his delightful skewering of our industrial model, he not only reminds us that the traditional curriculum is wildly unhelpful, he traces its origins to the desires of late 19th century policy makers to prepare a small percentage of learners for academia and the professorship, another small batch, the would-be doctors, lawyers and generals, and the rest for work and various levels of drudgery.

So began my long road of nagging doubts about the effectiveness of the traditional “math, science, history and English” line-up. My experiences as high school principal, college professor, school coach and consultant repeatedly unmasked school as limiting and often discouraging. At each stop along the way I was reminded me that people crave connections to their own “mysteries”, want to ask their own questions and chase big ideas, to find out more about things that really matter, not bounce around each day in a world carved into four or five thin slices.

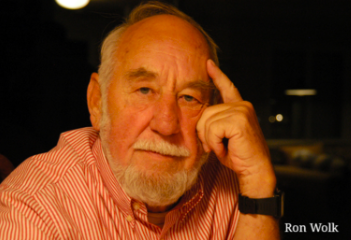

In agreement, and likely somewhat out of pity, a good friend, the late and great Ron Wolk, founder of Education Week (he was an early and persistent Jiminy Cricket of our disappointing “standards” movement) urged me to read Marion Brady’s work. Brady’s rich library of thinking on curriculum and standards added perspective and substance to my own from-the-trenches critique. See link.

That talk with Ron, who had his own rich legacy, inspired me to put my mind in a more focused way to contributing to school redesign. Serious redesign. The kind we imagined with Ted in the early 90’s. Not the silver bullets we’ve seen come, go, and repeat themselves --mastery learning, “PBL”, “blended” learning, competency-based instruction. They’re helpful but insufficient, adaptive approaches that accept most of the current “arrangements” of school. Our schools need the kind of redesign that doesn’t skirt the core issues and problems of our school “architecture”. I wanted to surface the hurtful impact of our industrial approach to school on learners and families, issues such as the false correlations between time and learning, the smothering limitations imposed by age-alike cohorts and overly simplistic cognitive and social/emotional development paradigms, reductive concepts of the locus of learning, and above all, the CURRICULUM. The curriculum that’s like carbon monoxide, that puts us to sleep without our knowing. A curriculum whose origins we can’t cite, that seems to have no agreed-upon aim or over-arching purpose and disregards the seamlessness of human perception. As Brady points out, our traditional curriculum thinking "accepts short-term recall rather than logic to access our memory banks, has few criteria for determining the relative importance of what' being taught, relates only occasionally to real-world experience, and fails to encourage creative thought".

I had a breakthrough moment in 2013. I had the good fortune to read a short yet especially thoughtful article, “Synergies”, by G. Wayne Clough, then Secretary of the Smithsonian Institution. His insights in to the urgency of organizing human thinking in a collective effort moved and excited me just as they had inspired his colleagues and collaborators at the Smithsonian. Finally, here was a way of making sense of our intellectual efforts, our potential as social and thinking creatures, and doing so in a way to make for a better planet and a better “civilization”. See link.

The Grand Challenges presented themselves immediately to me as a framework for re-igniting the passion and curiosity kids bring to the early grades but which are mainly lost as they learn to conform and to please, solving predetermined puzzles, a framework that can help us dig out from under the glut of competencies, do-now's, etc. that no one wants to come to grips with, but which is link here to Gallop poll putting kids to sleep.

Over the past two years, my ERC colleague Katrina Kennett and I and a small but growing number of teachers and schools we work with are helping us to deepen our understanding of the potential of The Grand Challenges. We’ve developed powerful visual provocations and entry events that correlate to the Grand Challenge topics and issues, as well as new tools to organize and expand the learning environment. We have imagined a unique learning landscape and developed a glossary of terms that explain those new structures and practices. Our “New Architecture of Learning” includes the elements of an ecology that can sustain more robust learning and activate powerful affinities among people, places and ideas, in the spirit of the original Grand Challenges.

Along the way, we’ve also learned that dissatisfaction with the traditional curriculum is not unique to us, is quite long-standing and comes from a wide variety of historical figures and intellectual fields. Link here.

This new collective energy gives us increasing hope that people can begin to slowly put aside our tired approach to “curriculum” and replace it with explorations and activities that use the Grand Challenges as a framework for learning, activities that erase some of the unhelpful boundaries and structures that inhibit passionate learning. Whether you use it in an existing unit of study, as a larger scaffold, as an alternating curriculum, or as your basic framework, you’re helping us move the dial.

White Mountains Regional HS STEAM Innovation Academy

So, if you’re ready, here’s the Grand Challenges “primer” you’ve been asking for, link below. Check it out. Imagine new, place-based, YES IN MY BACKYARD additions to the Challenges that resonate where you are and far beyond. Join our network, connect with others and help us move forward to meet the needs of our people and planet! Link here to see primer.