Some time ago I had the pleasure of writing an article for Phi Delta Kappan, entitled “Connecting the Dots” about the emerging understanding of the power of visual literacy, which included commentary on the work of graphic design doyen Kristina Lamour Sansone. Her stellar work with classroom teachers had always impressed me, and I was happy to recently learn that, beyond her broad set of design assignments and consulting both here and abroad, she’s re-booting her work with schools. Those allured by “design thinking” have made lots of promises but have had little impact in public education, so the re-emergence of Design Instinct Learning is really good news.

Recently, as part of that reboot, Lamour Sansone was tweeted at the 2020 AIGA National Design Conference speaking about how Cheryl D Holmes Miller’s work has influenced her own practice and understanding of the field and serves as a touchstone for her anti-racism and equity work.

I’ve had my frustrations with the “design” conversation and its billing as “the” solution. Just google “design in education” and you’ll get page after page of resources — people who will help guide you through a transformative processes, “change by design” deep dives that will bear solutions reaching into the arts, instructional technology, construction of new facilities, STEM (of course! that’s where the money is), and even in school district administration, of all things. As expressed recently in Atlantic magazine, “there are many flavors, colors, and brands of design thinking for educators to choose from”. So, one must ask, how come I haven’t seen it making much of a difference in classrooms? The noise level is high, the impact not so much.

Data visualization by Brandon Waybright referenced in Print Magazine titled Black Designers: Forward in Action (Part IV) by Cheryl D. Holmes Miller

In 2009, Tim Brown’s Change by Design opened the floodgates for bringing “design thinking”, “design innovation”, “design strategies” into education (and most everywhere else). Almost overnight, if you didn’t include the word design, one couldn’t possibly create, innovate, or seriously attempt to address big challenges. By the early 2000-teens, it seemed everyone was hosting design thinking events, expounding on how they employed it as would-be leaders in the field. But it seemed to be an in-bred conversation with little impact on schools and classrooms. I wanted to see if I was missing something.

Digging deeper, more provocations began to appear. A presentation by Natasha Jen, speaking to other ground-level designers, rued the fact that the “design” fad had become just that —a fad— and core principles and practices had been lost. An Atlantic article, also surfaced familiar themes and I also read some of Lee Vinsel’s commentary as well. His distaste for the design rage is quite apparent.

Design thinking can make a difference, I want to be sure to add. It provides a helpful set of principles and practices. It can move us beyond our traditions and blind-spots. Its no panacea but we should be using it as part of our reimagining schools. And on occasion, I do see many of those ideas doing well in some early-years programs for those who can afford them, in arts-based lab schools, and in some independent and “American” schools abroad. But the question of why all these big ideas seem to be absent from instructional thinking in our “regular schools” has remained a personal irritant. So, a year ago when I heard similar recognition of those critiques from Lamour Sansone at a Froebel conference she had helped to organize —“Essential components of design education are not being understood and utilized nearly as well as they might in our schools”— I had a hunch, and a hankering, that she might have in mind to re-open her shop to schools and educators.

Lamour-Sansone’s Design Instinct Learning work is informed by the notion that schools are too often squandering helpful ideas and proven approaches, and that we have to bring them to bear in a serious and organized way. That is precisely what she learned to do some time ago, and now plans to get back to in a larger, more potent way with the reemergence of Design Instinct Learning, including collaborating with ERC as a part of our emerging Innovation and Redesign Network. And as mentioned above, she brings with her skill and expertise a strong commitment to anti-racism and equity and a new prominence in that dialogue among her expert peers and the younger, up-and-coming camp.

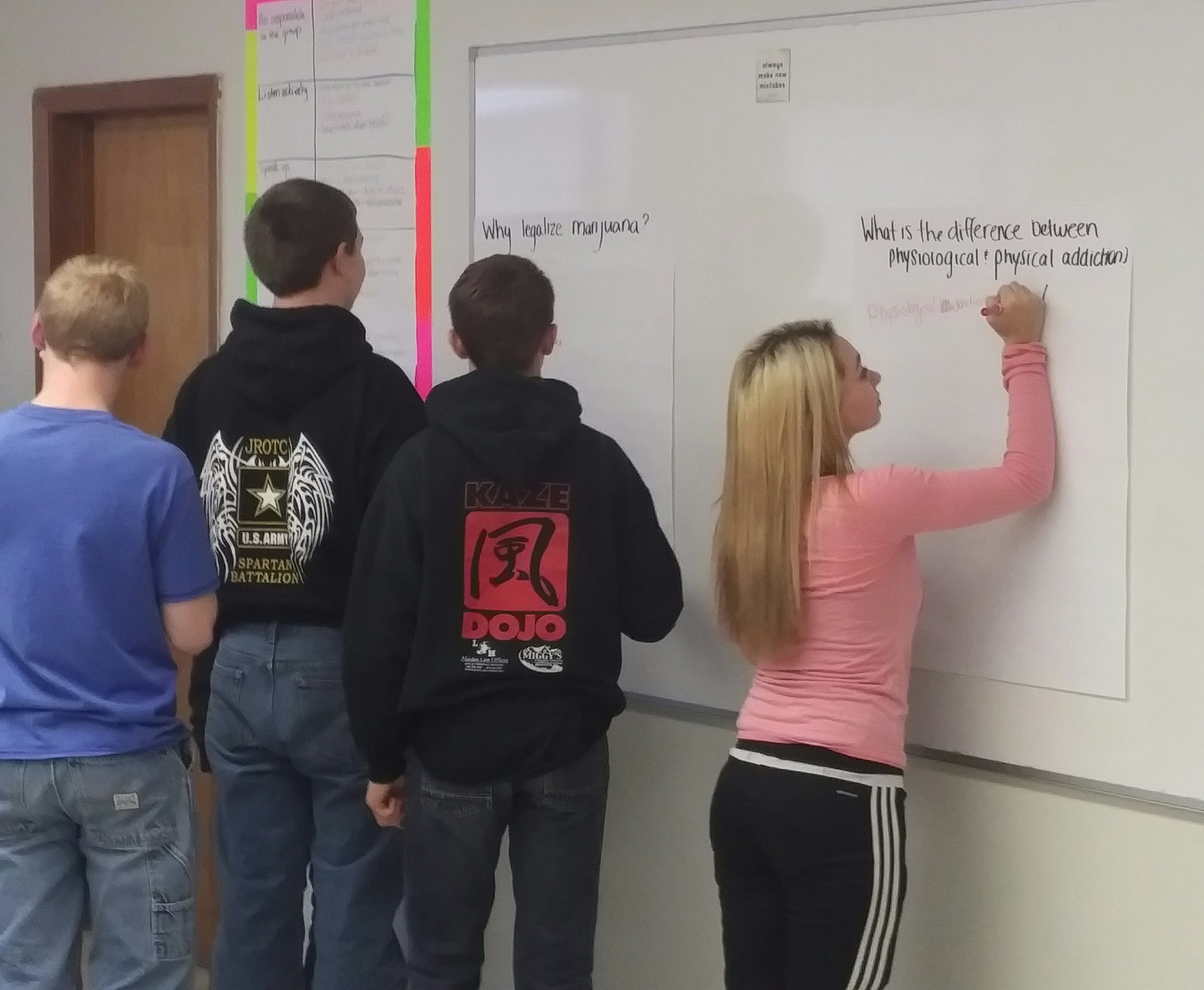

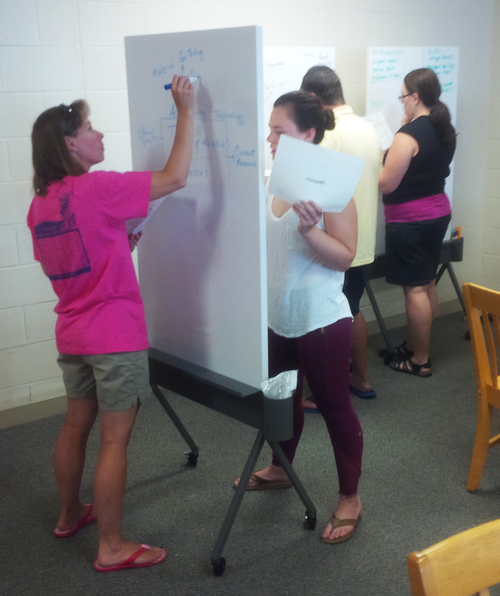

Lamour Sansone is gifted at working intimately with teachers and classrooms to boost the right stuff—engaging students through use of the imagery that is so prevalent on the screens and devices of this generation, helping them make connections and critique in disciplined ways their own work and the work of others. This kind of collaboration at high levels is core to the “21st century skills” stuff we want to see in schools, but which remains elusive. She shares:

“Educational reformers want to understand ‘design thinking’ and ‘studio thinking’, but it’s beautiful complexity cannot always be codified. Most approaches I see adapted for K-12 classrooms do not recognize or give space to the pedagogical listening, deep observation, visual research and acuity, and critical analysis found in a bona fide design studio critique. Moreover, it’s not solo work. Teachers need critical friends, intellectual and visual learning advocates, in the classroom to first recognize, then draw out their design instincts. Those instincts inhabit all of us, and they can be cultivated in school on the page, screen, classrooms outdoor/indoor.”

Lamour Sansone has brought her methodology to schools in New Haven, Austin, San Francisco, Providence, and to Boston, during their dynamic years of High School Renewal and Pilot Schools. Her compelling “case studies” from each collaboration show the breadth and depth of her work, as well as the impact of her approach on classroom learning. Her work in urban classrooms has shown her ability to help teachers find the key elements of “design instinct” that draw students in, prods them to make connections, sparks their curiosity for more examples and deeper exploration. Hers is the kind of work that makes good on many of those unkept promises mentioned above. DIL offers concrete ways to integrate much of the best thinking and practices from these arenas into planning for and teaching in public sector classrooms.

Social Justice Academy Humanities teacher Carole Teague’s, story is highlighted in Lamour Sansone’s, “Using Strategies from Graphic Design to Improve Teaching and Learning”.

Lamour Sansone would be modest about her accomplishments, insisting that most, if not all, educators carry with them a design instinct, albeit it’s often been largely put to sleep by experiences moving up through the grades as visual literacy, artistic thinking and design concepts drop away from “academics”. Her job she believes, through interviews, observations and analysis, is to surface that instinct, that voice and vision, in adults:

“I cultivate these instincts using modern design teaching continually tested in professional art and design schools and studios. Unlike one common myth, good design doesn’t always mean to simplify. Good design can be messy and circuitous. It suggests making the user curious, it doesn’t over-simplify but it also doesn’t overtell”.

One thing I’m particularly interested in, especially in the time of COVID-19 is the powerful interplay of nature, thought, and feelings. More attention is now being paid to the field of biophilic design and its potential in architecture, planning and beyond, utilizing the framework it offers for relating the human biological science and nature. Lamour has really embraced that potential, and her synthesis of the work of Rhoda Kellogg and the emerging influence of biophilic design is typical of her ability to integrate important concepts and ways of seeing into her mental framework for working with front-line educators. She explained to me,

“Rhoda Kellogg's theory and the ideas behind biophilic design share the same belief that living things need structure to survive and make meaning within. Think highways, the grid on a newspaper page, honeycombs, camouflage, a winding river. These are all grid structures for living, for the natural world. Children naturally draw within these structures This synthesis between and among text, image, sound, and movement as one simultaneous language is the essence of Design Instinct Learning -humans making meaning through structure and analysis. We can't survive without street signs in urban planning, web interface, restoring our bees, birds and threatened species, air traffic control, etc. Graphic design concepts allows learners to speak across these languages using these structures to communicate visually, and I would argue, adopt a language that is universal and cross-cultural.”

Besides her work as an esteemed professor teaching in a variety of design fields and in several institutions, I recently found her exploring new approaches to support teachers who work with new-to-our-country English Language Learners. So many of those students have come recently from countries that offer inconsistent schooling, at best. Others have seen crime, gang warfare, poverty, or estrangement from loved ones. Worksheets and multiple choice don’t do the job of inviting them into intellectual endeavor. These are young people in need of more sophisticated pedagogies to bring them more rapidly and successfully into both academic programming and into the new culture into which they’ve been catapulted.

The critical thinking capacities that derive from the Design Instinct Learning approach also come with key PYD (Positive Youth Development) aspects of self-expression and commentary, active participation and mastery. That’s a key reason her work with teachers consistently gets results and I’m envisioning the field of English Language Learning being dramatically improved by beginning to more deeply understand and employ Lamour Sansone’s experience and expertise.

ERC is proud to renew our partnership with Design Instinct Learning, one that will seek out opportunities to bring this generative thinking into schools and classrooms and to build momentum for improving learning and youth development. You can visit her website here designeducator.com and as always we here at ERC educationresourcesconsortium.org are thrilled to connect and make introductions.

Dr. Larry Myatt

Co-Founder